Oral histories of the early breeders and ranchers provide a valuable context or framework for the breed. The pioneer breeders were not dog people. They were sheep ranchers whose livelihoods depended on the dogs. They didn’t care what color the dogs were or if they came from Spain, Timbuktu or Australia. There were unique qualities associated with the Basque and Spanish dogs that didn’t exist in other breeds.

Early foundation bloodlines were based on dogs from the Pyrenees Mountains. Both Spain and France grazed large flocks of sheep (and goats) on Andorra’s vast mountain pastures each summer. According to Roderick Peattie, writing in the Geographical Review, 1929, “The Pyrenees are not as sharp a divide between France and Spain as they are generally credited with being. At places along the summit of the range it is difficult to judge where the water divide may be. The flocks and herds of the two people mix here” (1929). 2

Juanita Ely, a sheep rancher and one of the oldest documented breeders of record affirmed, “The blue Australian Shepherd dogs first came to Australia from the Great Pyrenees on the Spain side, as it is a small country with Andorra, a little country lying between Spain and France of only 191 square miles. There isn’t much work [in Andorra] for the boys to do so they take their little blue dogs and go into Australia to herd sheep. A lot of these boys are Basque, coming from a region in north Spain.”

She also noted, “The wool from Australia was finer and much longer staple than we had here in the United States so we brought boatloads of sheep from Australia to Seattle, Washington. The Basque herder and his little blue dog coming over to care for the sheep on the boats and so started working in that vicinity, then located in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. As these dogs were brought to the United States from Australia, we speak of them as Australian Shepherds.”3

Those “little blue dogs” (les petits bleus) so to speak were associated with Idaho, the Pacific Northwest, California and Colorado. Teddy, the little blue dog Juanita Ely got in the 1920s, was the first blue dog she had ever seen. The teenager from whom she purchased Teddy was Andorran, but he identified himself as Basque.

It wasn’t until around WWII that the blue dogs started showing up in significant numbers and ranchers started breeding them in earnest. Feo was brought to the United States from Spain with a contract herder who worked for the Warren Livestock Company* in the 1950s. Juanita Ely bought the little blue dog. By 1960, our friend, Joe Fernandez got him from Juanita and was using him, along with our little Goody (Goodie), in Southern Colorado and Northern New Mexico, where he was running several bands of sheep consisting of 1,500 head per band. 4

According to Ken Duart, an early California breeder, he acquired Lita, an early foundation bitch, from a Basque shepherd who brought her directly from Spain. She was an attractive blue merle female (with one blue eye). She had a moderate coat and a long tail. He said a sheepherder who had a bunch of sheep at Rolf’s Ranch in the San Miguel area had friends that came to California from the Basque sector of the French and Spanish border. When they came to the United States, they brought two dogs, which they were allowed to bring as tools of their trade without quarantine. The time was either late 1959 or early 1960.

The Basque and Spanish dogs in California and in Arizona figured significantly in the breed’s early foundation. Eloise Hart, ASCA’s first president, was ten years old when she acquired her first dog in 1930. Eloise said, “He was a stocky, bob-tailed, brown dog with an infinite capacity to learn. Blanco came to California from the Basque sheep country in Spain. His owner was forced to forfeit him, as payment for some minor violation, to a lawyer neighbor of ours when we lived near Wilshire and Vine in Los Angeles.”

Wood’s Dandy (Finley’s Texas Bob X Moreno’s Blue Bitch AKA Valdez Female) was bred by the Moreno family from the dogs they brought to California from Spain. Fletcher acquired Dandy from Chule Valdez. Maryland Little’s Honey Bun was considered “the Spanish type.” She was from the Graatz ranch in Colton, California, with several recorded generations preceding her. McConkey’s Sir Blue Silver was from the Ortega dogs and McConkey’s Tiger Britches was from Maryland Little’s dogs. Maryland based her breeding program on Basque and Spanish dogs.

Ina Ottinger of Casper, Wyoming, stated that her parents imported two dogs from Spain in 1937. She had the original shipping certificates. She continued breeding that line of Wyoming ranch dogs into the middle seventies. She also acquired a little red merle male that looked just like Las Rocosa Sydney that was brought to the United States by a Basque sheep shearer during the World’s Fair in Seattle. When the herder left to go back home he couldn’t take the dog with him so she bought him. Some of the offspring are found in pedigrees as Wyoming Ranch dogs. 4

By 1974, there were only 16.5 million sheep in the United States. The sheep industry continued to decline and Basque herders were no longer recruited from Spain. However, the foundation for the breed was already established from a relatively small group of dogs including Ely’s Feo, which is documented by registration. Feo went on to sire Hartnagle’s Goody, the beautiful little blue female (later registered as Wood’s Blue Shadow) who is behind the pedigrees of countless Australian Shepherds today, including the Dr. Heard’s Flintridge, Hartnagle’s Las Rocosa, and Fletcher Wood’s foundation bloodlines.

Unfortunately, as we’ve explained before, under the old registry system, each time that a dog changed ownership, the previous owner’s name was deleted and the new owner’s name was entered as the prefix to the dog’s name. Thus, part of history becomes obscured. Take Ely’s Spike for example. On some pedigrees, Ely’s Spike is listed as being sired by Sisler’s Spike, when in fact; Sisler’s Spike and Ely’s Spike are one and the same. Juanita Ely got Spike from Gene Sisler (Jay’s brother). Spike’s sire and dam are listed as “Unknown.” The old-timers may not have known the name of the sire and dam, but they knew where they came from. Spike came to this country from the Pyrenees Mountains with a Basque herder. Spike had a harsh coat very much like the dog pictured with the sheepherder on the Drumheller ranch on page 32 in The Total Australian Shepherd: Beyond the Beginning.4 Sometimes when the dog changed hands it became foundation registered with a totally different name and “Unknown” ancestry. This activity all took place in the early years from the 1940s to the 1960s when the foundation dogs were first being registered as a breed. Even though their names appear in pedigrees, many of the early dogs weren’t registered. They had already lived and died.

For more on the Australian Shepherd see also: All About Aussies: The Australian Shepherd from A to Z (Alpine Publications).

Sources

2. Peattie, Roderick, “Andorra: A Study in Mountain Geography,” Geographical Review, vol. 19, no. 2, 1929.

3. Douglass, William A., Basques in Australia, Basque Studies Program Newsletter, issue 18, 1978.

4. Hartnagle, Carol Ann, Hartnagle, Ernest, The Total Australian Shepherd: Beyond the Beginning, Hoflin Publishing, 2006. http://www.lasrocosa.com/totalaustralianshepherd.html.

Copyright © 2010 by Jeanne Joy Hartnagle-Taylor and Ernest Hartnagle. All rights reserved.

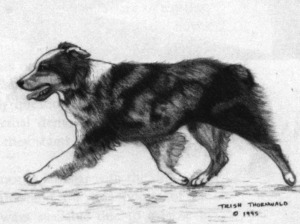

When the Australian Shepherd shifts from the walk into an easy, slow trot, the gait is called “collected.” In the “extended” trot, the legs reach out to increase stride length and speed. (The length of stride is measured from the place where one paw leaves the ground to the place where the same paw again strikes the ground.) When a period of suspension occurs between the support phases and propulsion, the gait is referred to as a “flying” or “suspended” trot.

When the Australian Shepherd shifts from the walk into an easy, slow trot, the gait is called “collected.” In the “extended” trot, the legs reach out to increase stride length and speed. (The length of stride is measured from the place where one paw leaves the ground to the place where the same paw again strikes the ground.) When a period of suspension occurs between the support phases and propulsion, the gait is referred to as a “flying” or “suspended” trot.